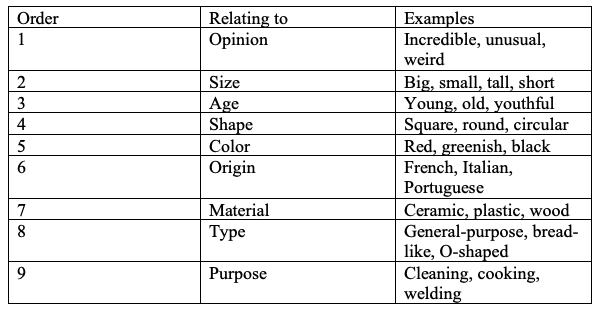

1. Adjective order

Have you ever asked yourself why we say, ‘the big, brown bear,’ instead of ‘the brown, big bear?’ What about the sentence, ‘It was made of a strange, green, Japanese material?’ For some reason, it just sounds weird if instead we say, ‘It was made of a green, Japanese, strange material,’ or even, ‘It was made of a Japanese, green, strange material.’ This is true because the adjectives preceding a noun have to follow a certain order depending on what they relate to:

So, in the sentence ‘It was made of a strange, green, Japanese material,’ strange = opinion (1), green = color (5), and Japanese = origin (6). Since the adjectives occur in the correct order, the phrase just sounds right to us, even if we had no idea that this grammar rule existed!

2. Ablaut Reduplication

If you’re like me, you might’ve just spent the last five minutes looking for exceptions to rule number one. And there are a few. For example, though Little Red Riding Hood rolls perfectly off the tongue in accordance with size before color before purpose, Big Bad Wolf breaks the adjective order rule, putting size in front of opinion. But it’s no accident. For any native speaker, Bad Big Wolf, though following the correct adjective order, simply grates the ears. That’s because it’s breaking rule number two, that of ablaut reduplication, which overrules the adjective order rule in this case.

Abluat Reduplication is when a word or sound gets repeated, sometimes with an altered consonant, as in lovey-dovey, and sometimes with an altered vowel, as in mish-mash, wishy-washy, and tick-tock. The rule goes that if there are three words, as in ding-dang-dong or bish-bash-bosh, the order of the vowels has to go I, A. O. If there are only two words, then the first is I and the second is either A or O, as in hip-hop, tic tac, King Kong, ding dong, ping pong, chit chat, etc. This is a rule that can be credited entirely to human ingenuity and our predilection for melodious language. It is not, as it may appear, onomatopoeia. After all, every second that the hand on your clock moves, it is making the same noise, and yet we say tick-tock, never tock-tick or tick-tick. The same is true for a horse’s feet – they all make the exact same sound, but we always say clip-clop, not clop-clip.

3. The ‘kind of’ rule

Have you ever wondered why artists paint ‘still lifes’ and not ‘still lives?’ What about if you were inviting Julia Child’s family over for a barbeque? You would say you were inviting the Childs over, not the Children. Similarly, the hockey team from Toronto is called the ‘Maple Leafs’ rather than the ‘Maple Leaves.’ This is all true because of a grammar rule called the ‘kind of’ rule, which was discovered by renowned linguist Steven Pinker. The rule essentially states that since Julia Child is not a ‘kind of child,’ her last does not follow the irregular pluralization rule that normally changes ‘child’ to ‘children.’ Similarly, a still life is not a kind of life, but rather a kind of painting, and the Maple Leafs are not really a kind of leaf, but a hockey team.

4. The Animacy Hierarchy

This next rule is enough to drive any non-native English speaker crazy. Have you ever noticed that there are two ways of expressing possession in English? We say ‘my grandmother’s cat,’ and never ‘the cat of my grandmother,’ but then we turn around and say ‘the houses of Parliament’ rather than ‘Parliament’s houses.’ In languages such as Spanish or French, this difference doesn’t exist – all possessives are expressed using the ‘of’ construction (i.e. El gato de mi abuela, la chat de ma grand-mere). So, what’s going on here? Why does ‘the cat of my grandmother’ sound so inherently wrong?

Though very few native English speakers are aware of it, possessives are formed with reference to the animacy hierarchy. This hierarchy basically moves in decreasing order of humanness, going from human to animal to inanimate object. The closer to a human that the possessor of the phrase is, the worse the ‘of’ construction sounds. So:

‘my friend’s bike’ sounds better than ‘the bike of my friend’

‘my dog’s leash’ sounds somewhat better than ‘the leash of my dog’

‘my bike’s pedal’ sounds the same or worse than ‘the pedal of my bike’

There are a few exceptions, as in ‘Congress,’ which can be interpreted as an inanimate object (the steps of Congress), or as a group of people (Congress’ new bill), but I’m sure you already knew that, even if you didn’t know you knew it.

5. Why ‘abso-freakin-lutely’ and not ‘ab-freakin-solutely?’

If you’re a native English speaker, you’ve probably heard people emphasize a word or phrase by sticking an expletive in the middle of another word. But how does anyone know where the expletive goes? Well, there’s another rule at work here, which states that the inserted expletive should go right before the syllable with the most natural stress. That’s why we say ‘abso-freakin-LUTEly,’ ‘la-freakin’-SAGna,’ and ‘kalama-freakin-ZOO,’ and never ‘absoLUTE-freakin-ly,’ ‘laSAG-freakin’-na,’ or ‘kal-freakin’-amaZOO.’ This occasionally changes, like when the word has a negation prefix (un-freakin’-beLIEVable), but then, you already knew that as well, didn’t you?

As you can see, English is largely made up of rules that most of us don’t know that we know. And, contrary to what you might believe based on the few grammar rules that you do know of and sometimes get wrong, if you’re a native English speaker, you’re also probably an English grammar expert. So the next time you’re beating yourself up for forgetting the difference between your and you’re, just think of all the other grammar rules that you use seamlessly every day. And also, give a pat on the back to any non-native speakers you know. Getting all of this right, after all, is definitely no walk in the park.